Marie Olivier Sylvestre Manitouabe8ich (Manitouabeouich) (1624-1665) & Martin Prévost

Marie Olivier Sylvestre Manitouabe8ich (1624-1665)

Introduction

Marie Olivier Sylvestre Manitouabe8ich (also spelled Manitouabeouich, Manitouabewich, Manithabehich, or Manitouabewick) was a historically significant figure in early Canadian history. She is widely recognized as the first Indigenous woman to marry a Frenchman in New France (now Canada). Her life and heritage bridge Indigenous and European cultures during the formative period of Canadian history.

The name “Ouchistaouichkoue” appears in a citation where she served as godmother in 1642. Her Indigenous birth name was 8chista8ichi8e Manitouabe8ich (pronounced: Ouchistauichkoue Manitouabeouich).[1]

Origins and Early Life

Marie was born around 1624 (some sources incorrectly cite September 10, 1615, but without documentation). She was the daughter of Roch Manitouabéouich and Ouéou (also referred to as Outchibahanoukouéou or Outchibabanoukoueou). Her mother may have been “Outchibaliabanoukoueau,” mentioned by Father Lejeune as having children with Manitouabeouich.[1:1]

Cultural Heritage

Marie’s Indigenous heritage has been subject to debate. While some sources claim she was Huron or Abenaki, primary historical evidence supports her Algonquin origins:

- Father Hierosme (Jérôme) Lalemant identified her as Algonquin in a document dated May 10, 1661.

- Two notarized documents dated June 22, 1659, and March 20, 1668, signed by her husband Martin Prévost, confirm her Algonquin heritage.

- Les Relations des Jesuits (1610-1791) and Le Terrier du Saint-Laurent en 1663 indicate she was Algonquin.

It’s worth noting that some confusion may arise from the possibility that her father was Algonquin while her mother was Huron, or from the matriarchal structure of Huron society. The Algonquin Nation being a patriarchy, her father Roch Manitouabe8ich would, by default, also be Algonquin.[2]

The Number “8” in Indigenous Names

The number “8” in Manitouabe8ich represents a specific sound. In the early 15th century, the letter “w” was rarely used in the French alphabet. Instead, a small “u” would be placed above a “0” to represent this sound, and typographers later substituted this with the number “8” as the closest available character. Over time, this notation was replaced with “OU” (for example, Outa8ais became Outaouais).[3]

Adoption and Education

At a very young age, Marie was entrusted to Sieur Olivier Le Tardif of Honfleur, who adopted her and became her godfather. This arrangement was made out of great respect for Le Tardif. She was approximately ten years old at the time of her adoption.

Le Tardif ensured Marie received a European education, placing her with the Ursuline nuns of Quebec to be raised and educated in the French manner. She later lived with the family of Guillaume Hubou and his wife Marie Rollet (widow of Louis Hébert). This French education would have been unusual for an Indigenous person of that time.[4]

Baptism and Naming

Upon her baptism, she received three names:

- “Marie” in honor of the Virgin Mary

- “Olivier” in honor of her godfather and adoptive father, Olivier Le Tardif

- “Sylvestre” referring to “one who comes from the forest” or “who lives in the forest” (acknowledging her Indigenous origins)[5]

Marriage to Martin Prévost

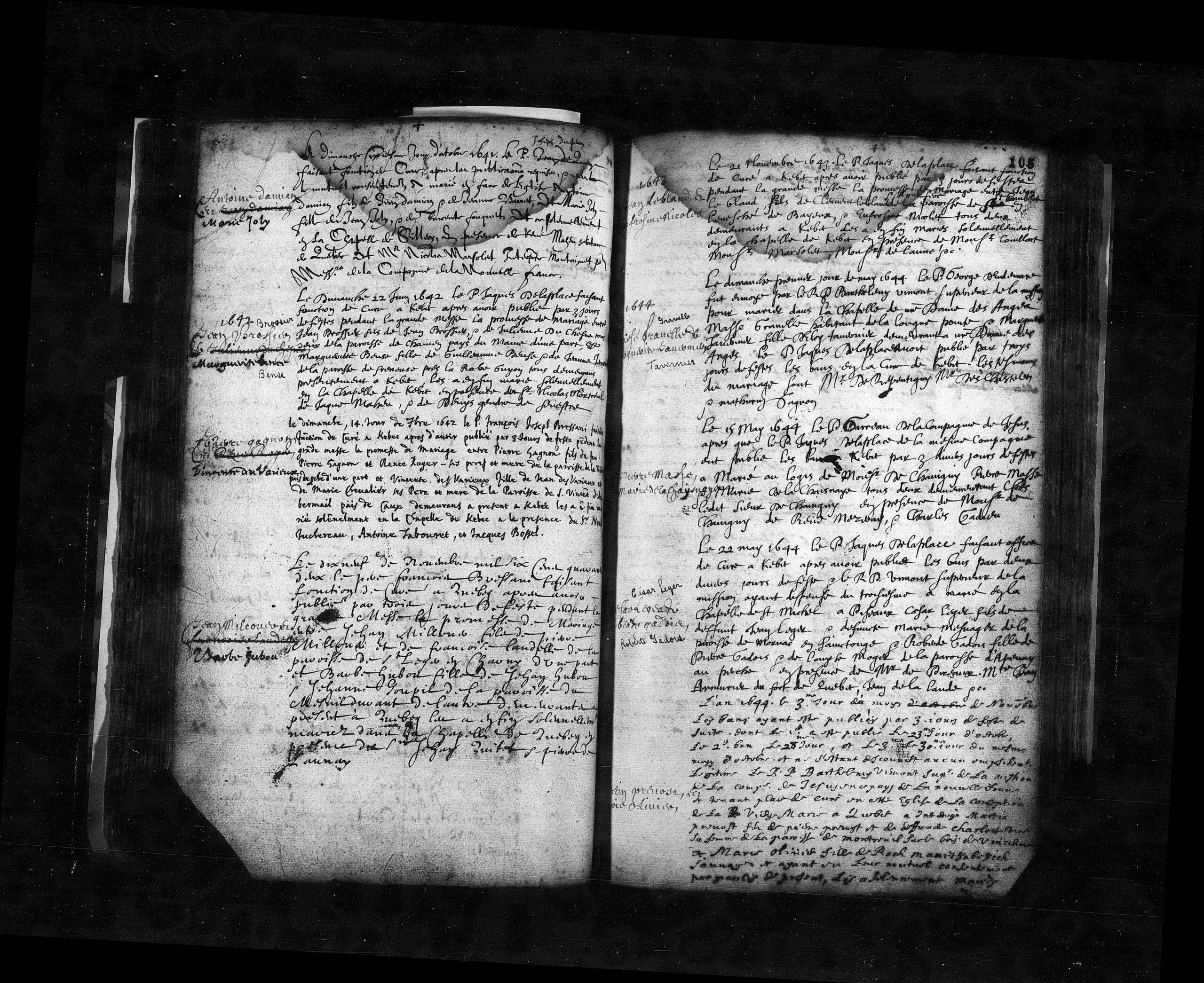

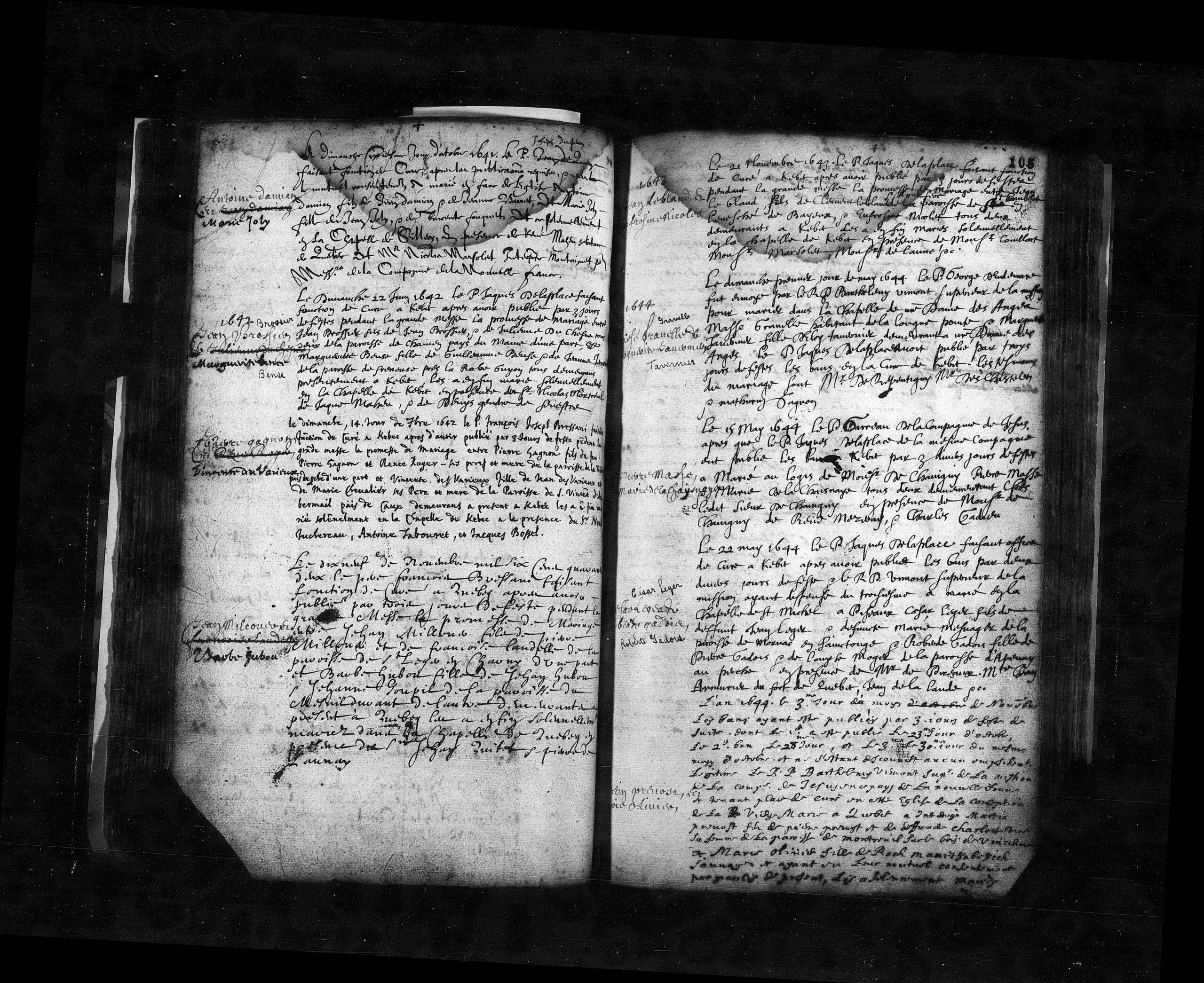

On November 3, 1644, at Notre-Dame parish in Quebec, Canada, Marie Olivier Sylvestre, aged approximately 20 years, married Martin Prévost, aged 33 years. This marriage is historically significant as it represents the first recorded marriage between an Indigenous woman and a French settler in New France.

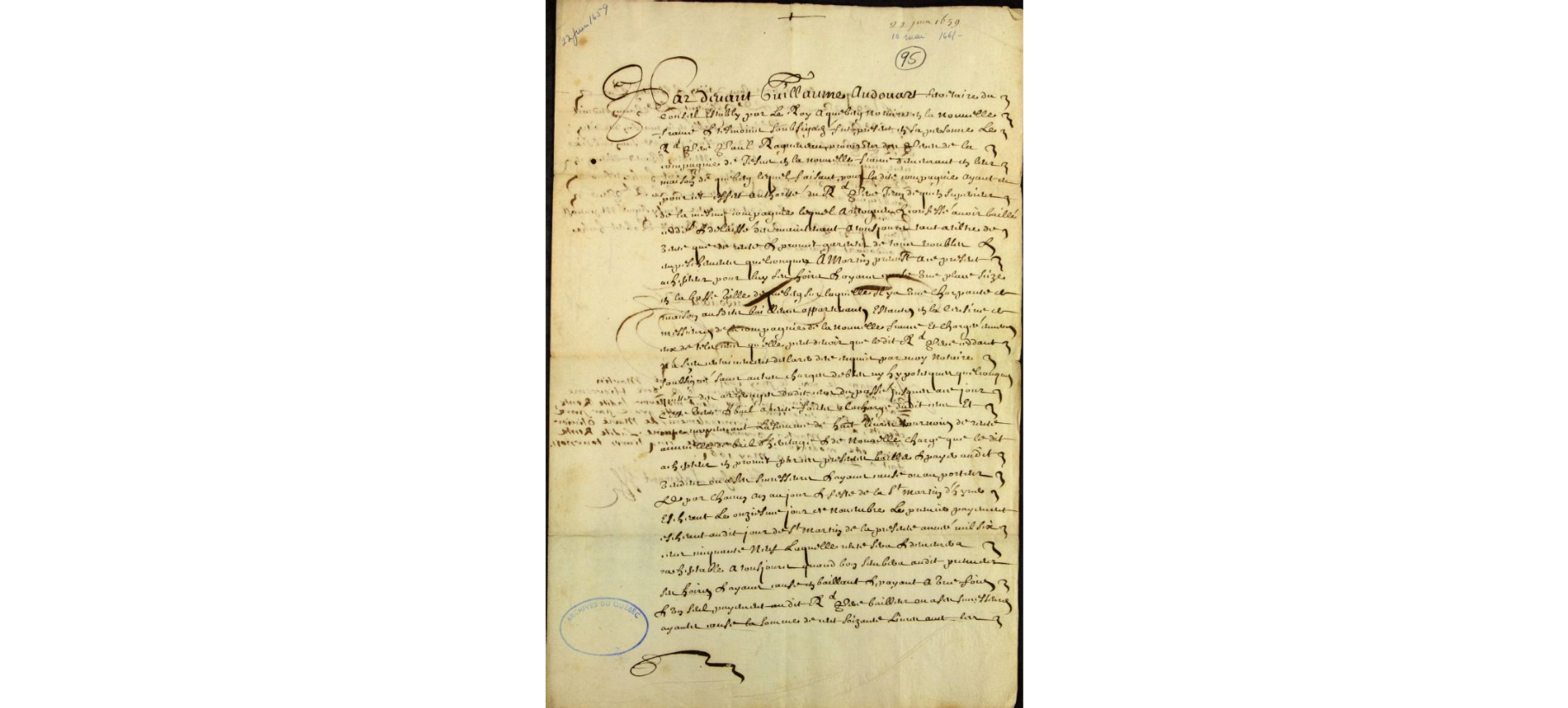

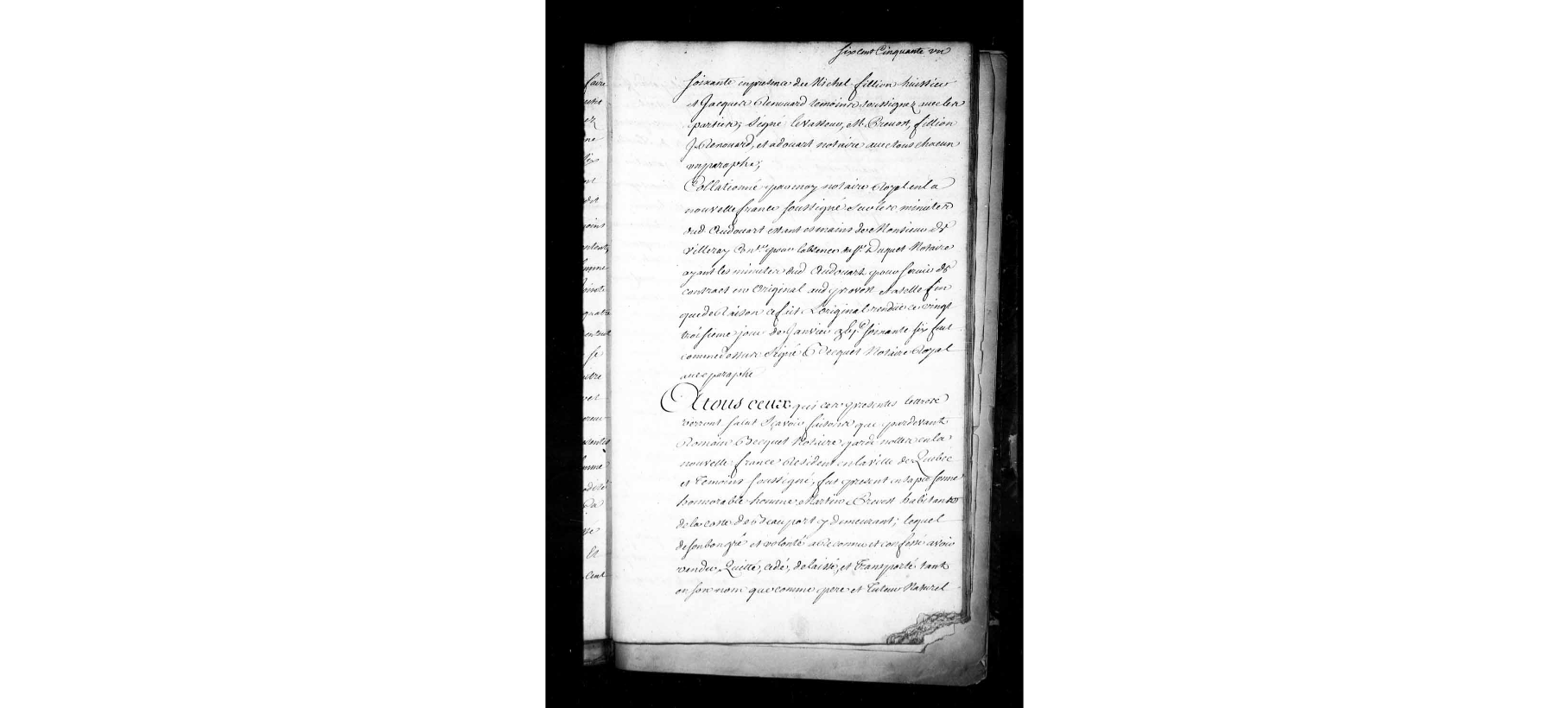

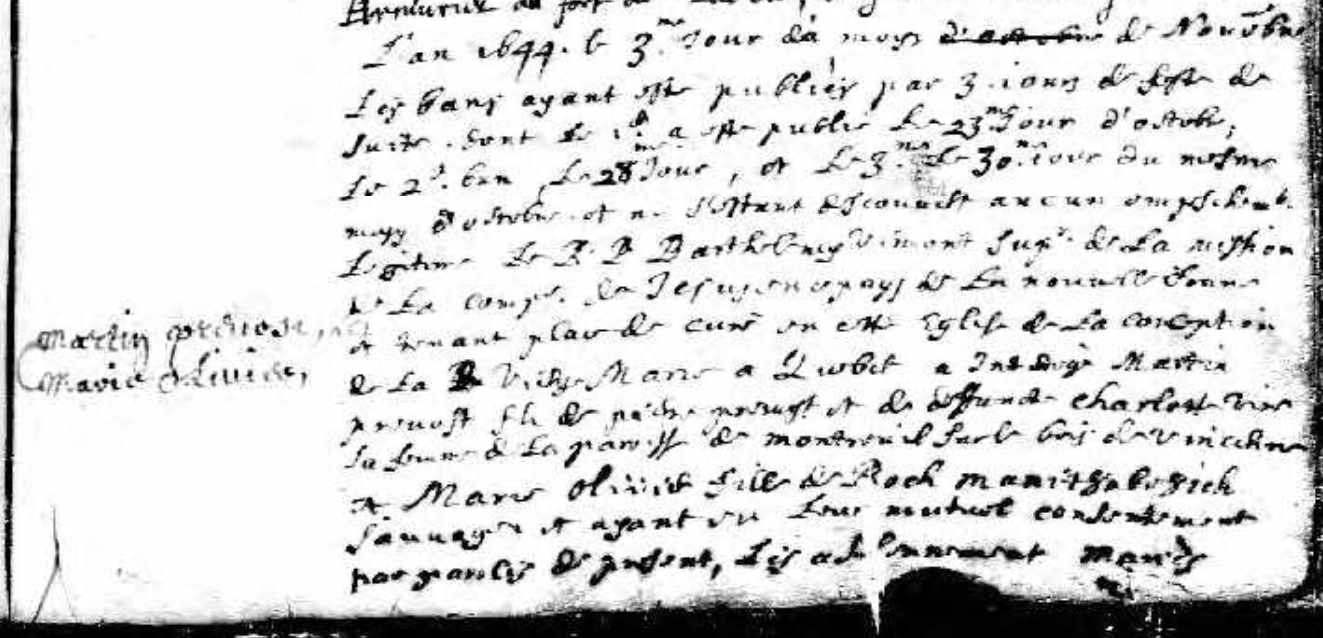

Marriage Certificate Transcription

Marriage of Martin Prévost and Marie Olivier. The year 1644, the 3rd day of the month of November. The banns having been published for 3 feast days in succession, the 1st being published on the 23rd day of October, the 2nd ban on the 28th day, and the 3rd on the 30th day of the same month of October, and no legitimate impediment having been discovered, Reverend Father Barthelemy Vimont, Superior of the mission of the Society of Jesus in this country of New France and holding the place of parish priest in this Church of the Conception of the Virgin Mary in Quebec, interrogated Martin Prevost, son of Pierre Prevost and the late Charlotte Vien his wife, of the parish of Montreuil Sur le bois de Vincennes, and Marie Olivier, daughter of Roch manit8abe8ich, a Native, and having received their mutual consent by present words, solemnly married them and gave the nuptial blessing in the Church of La Conception in Quebec, in the presence of known witnesses. Olivier Le Tardif and Guillaume Couillard of this parish.[6]

The marriage was witnessed by Olivier Le Tardif and Guillaume Couillard (Le Tardif’s father-in-law).

Children of Marie Olivier Sylvestre and Martin Prévost

Marie and Martin had nine children together:

- Marie Magdeleine Prévost (abt. 1647-abt. 1648)

- Anonymous Prévost (1648-1648)

- Ursule Prévost (1649-1661)

- Louis Prévost (abt. 1651-1686)

- Marie Magdelaine Prévost (1655-abt. 1662)

- Antoine Prévost (1657-1662)

- Jean Pascal Prévost (1660-bef. 1710)

- Jean Baptiste Prévost (1662-1737)

- Marie Thérèse Prévost (1665-1743)

Of their children, four survived to adulthood and married. Jean-Baptiste, Thérèse, and Louis married into prominent families of the time.[7]

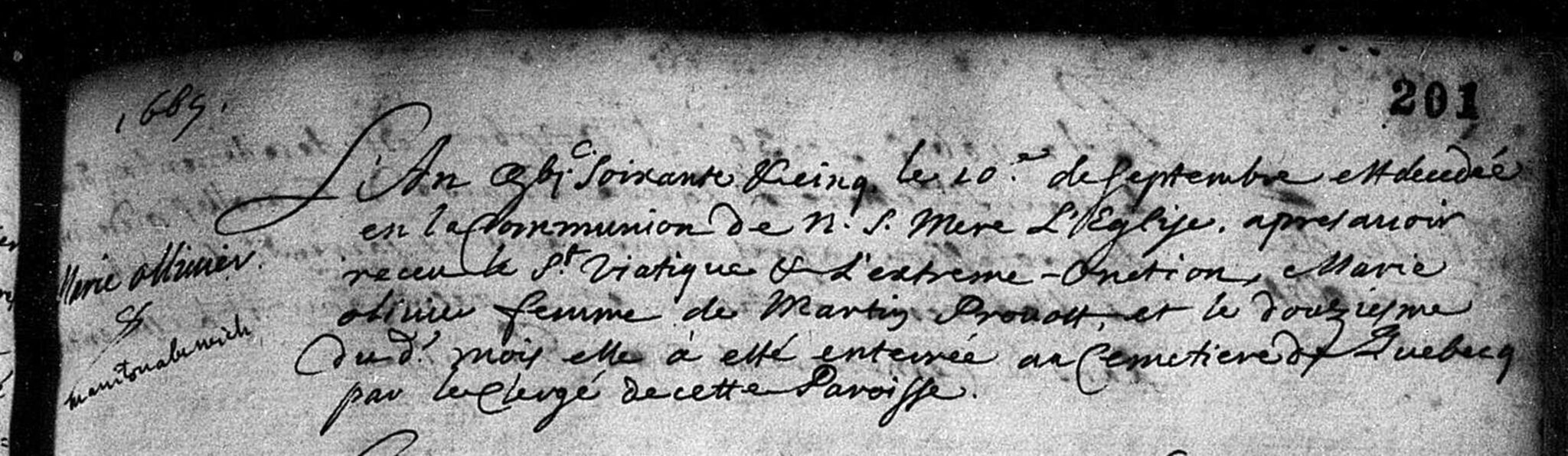

Later Life and Death

Marie Ollivier was present and signed the marriage contract of Marie Messange with Mathurin Chabot on November 3, 1661, in Beauport.[8]

On September 10, 1665, aged approximately 41 years, Marie Olivier Sylvestre Manitouabe8ich died in Quebec and was buried the same day in the Quebec cemetery. Her death occurred only a few months after the death of her adoptive father, Sieur Olivier Le Tardif of Honnefleur, who had passed away on January 25 of the same year.[9]

Martin Prévost After Marie’s Death

Following Marie’s death, Martin Prévost remarried in 1665 to Marie d’Abancourt, who was the widow of Jean Joliet and Gefroy Guillot.

On March 20, 1668, a sales contract was executed by “Martin Provost, inhabitant of the coast of Beauport, widower of the late Marie Olivier, his first wife, Algonquin Native woman, [both in his name and as guardian of their minor children],” selling to Nicolas Gauvreau, master gunsmith and arquebusier of Quebec, a plot of land and a small house located in the Lower Town of Quebec (Notary Romain Becquet).[10]

Martin Prévost died on January 26, 1691, in Beauport.

Legacy

Today, the marriage of Martin Prévost and Marie Olivier Sylvestre Manitouabe8ich is honored in a park dedicated to their union in Quebec. Their descendants have continued through multiple generations, connecting many modern Canadians to this historically significant couple.

The Jesuits Relations relates one of their visits to one of the original families of Sillery (i.e. Algonquin) in which they speak of a little boy, brother to Marie Olivier.[related documents below]

Genetic Heritage

An mtDNA test appears in the research group Québec ADNmt / Quebec mtDNA indicating haplogroup C1c, a Native American haplogroup, confirming Marie’s Indigenous maternal lineage.[11]

Historical Context: Roch Manitouabe8ich and Olivier Le Tardif

Roch Manitouabe8ich (Marie’s Father)

Roch Manitouabe8ich was employed by Samuel de Champlain for eight years before traveling into Canada’s interior with Olivier Le Tardif. He was a converted Christian, baptized by French missionaries and named Roch in honor of St. Roch, a patron saint.

As a team, Le Tardif and Manitouabe8ich often ventured deep into the Canadian wilderness to make contact with Indigenous settlements and nomadic groups. They encouraged these communities to use the facilities of the various trading posts that had been established for the fur trade.

Roch Manitouabe8ich eventually settled into a more domestic lifestyle in the Indigenous settlement at Sillery near Quebec.[12]

Olivier Le Tardif (Marie’s Adoptive Father)

Olivier Le Tardif was born in Honfleur, France, in 1601. He was a close companion of Samuel de Champlain and became a trusted interpreter after learning the languages of the Huron, Algonquin, and Montagnais peoples.

Le Tardif served as the personal representative and interpreter for Samuel de Champlain. From 1626 to 1629, he was stationed in Quebec and involved in the fur trade. He received land near Quebec in 1637 and expanded his holdings over the years.

After eight years as a local and field clerk, Le Tardif was promoted by Champlain to become the first clerk (equivalent to secretary-treasurer) of the fur trading company. He then settled into a more stable lifestyle, directing the “internal affairs” of the Company at the main office in Quebec (Lower Town).

The bond of friendship, trust, and loyalty between Le Tardif and Roch Manitouabe8ich remained strong throughout their lives, even as they lived in different environments.[13]

Fur Trading System

Samuel de Champlain established a comprehensive fur trading system, which Le Tardif and Manitouabe8ich helped implement. This system included:

- Trading posts that served as intermediaries between trappers and the Company

- Three types of trappers:

- Trappers licensed by Company authorities

- Itinerant unlicensed trappers known as “Coureurs des bois”

- Indigenous people who trapped and traded with the Company

These trappers would barter their furs at trading posts, typically choosing the one closest to their hunting grounds. The trading posts offered a depot where trappers could exchange furs for traps, knives, clothing, and other goods. Indigenous people often bartered for blankets, mirrors, hats, and colored beads to adorn their traditional costumes and headdresses.[14]

Sources

- “MANITOUABEOUICH,” primary source document. ↩︎ ↩︎

- Les Relations des Jesuits (1610–1791) and Le Terrier du Saint-Laurent en 1663, confirmed by notarized documents dated 1659-06-22 and 1668-03-20. ↩︎

- Histoire du Quebec sous la direction de Jean Hamelin, Edition France Amerique, pages 30 et 32 (Les Amerindiens au XVIe siecle). ↩︎

- Société d’Histoire – Marie Olivier Sylvestre Manitouabe8ich. ↩︎

- Binet Guimont, Suzanne #1767 (ACGS Member) Issue #23, the Genealogist. ↩︎

- Family Search – Marriage – Martin Prévost – Marie Olivier Sylvestre – Parish record. ↩︎

- Memoires de la Society Genealogique Canadienne Francaise, Volume 7, page 118; Volume 12, page 8; Volume 25, page 16; Volume 48, pages 33-36. ↩︎

- FamilySearch: Guillaume Audouart, Records, Files 838-1263 (Nov. 23, 1659 – Oct. 22, 1663), Family History Library, United States & Canada 2nd Floor Film #2371065, Image Group Number (DGS) 8710879, pgs 741-744/1431 marriage contract Mathurin Chabot – Marie Messange. ↩︎

- Burial of Marie Olivier wife of Martin Prévost, Parish record. ↩︎

- BAnQ Digital Archives, March 20, 1668, Textual Archives, E1,S4,SS1,D345,P8, Intendants Collection, Government Publications and Archives. ↩︎

- Québec ADNmt / Quebec mtDNA – mtDNA Test Results for Members: Marie Olivier Sylvestre (Manitouabeouich) Prevost, Canada. ↩︎

- The Jesuit Relations and Allied Document Volumes 5-6, page 287 (Olivier LeTardif), page 288 (Manitouabewich, Marie) Volumes 72-73, page 124 (Manituouabewich, Marie). ↩︎

- Dictionary of Canadian Biography: Honorius Provost, “PRÉVOST (Provost), MARTIN,” vol. 1, Laval University/University of Toronto, 2003. ↩︎

- Trudel, Marcel – La population du Canada en 1663, Page 352 (Manitouabewich, Marie Olivier: 27s., 248). ↩︎

ManyRoads Resources:

Primary Sources (Firsthand Accounts):

- The Jesuit Relations: These are a treasure trove of information about life in New France, including interactions with Indigenous peoples, missionary activities, and daily life. They often mention individuals like Le Tardif and provide context for the period. (Search online for digitized versions or look for scholarly editions.)

- Samuel de Champlain’s Writings: Champlain’s journals and accounts are essential for understanding the early years of New France, as he was a key figure in its founding and exploration. (Look for published editions or digitized versions.)

- Notarial Records: These records (contracts, land grants, etc.) can provide details about individuals’ lives, property ownership, and family relationships. The Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec (BAnQ) is an excellent resource for these.

- Early Parish Registers: Church records (baptisms, marriages, burials) are vital for genealogical research and provide demographic information. Again, the BAnQ is a good place to start.

Secondary Sources (Historical Analyses):

- “New France” by Francis Parkman: Although older, Parkman’s multi-volume work is a classic and provides a comprehensive overview of the era. (Check Internet Archive or Project Gutenberg.)

- “History of Canada” by François-Xavier Garneau: Another classic 19th-century history of Canada, offering a perspective on early French colonization. (Likely available on Internet Archive.)

- Modern Scholarly Works on New France: Look for books and articles by historians specializing in 17th-century New France. University presses and academic journals are good sources. Search library catalogs or online databases like JSTOR.

- Biographies: Biographies of key figures (Champlain, Le Tardif, etc.) can provide detailed information about their lives and contributions.

Genealogical Resources:

- WikiTree: WikiTree can be a helpful starting point for genealogical research. However, always verify information with primary sources.

- Ancestry.com (or similar sites): These sites can be useful for tracing family lineages, but access often requires a subscription.

- American-Canadian Genealogical Society: This society may have resources specific to French-Canadian families.

- Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec (BAnQ): The BAnQ is a crucial resource for genealogical research in Quebec, with access to vital records and other documents.

Other Resources:

- Dictionary of Canadian Biography: This online resource provides detailed biographies of significant figures in Canadian history.

- Museums and Historical Sites: Visiting museums or historical sites related to New France can bring the period to life and provide valuable context.

- Academic Journals: Journals specializing in Canadian history or early American history are good sources for scholarly articles.

Tips for Research:

- Start with secondary sources: These will give you a good overview of the period and introduce you to key figures and events.

- Move to primary sources: Once you have a good understanding of the context, delve into primary sources for firsthand accounts and original documents.

- Cross-reference information: Always compare information from different sources to ensure accuracy.

- Be aware of biases: Historical sources can reflect the biases of their authors, so it’s important to consider different perspectives.

- Use library resources: Librarians can be invaluable in helping you find relevant materials and navigate historical research.

Do you benefit from our articles and resources?

Your support, through donation or affiliate usage, allows ManyRoads to remain online.