François Banliac dit Lamontagne & Marie-Angélique Pelletier

Introduction

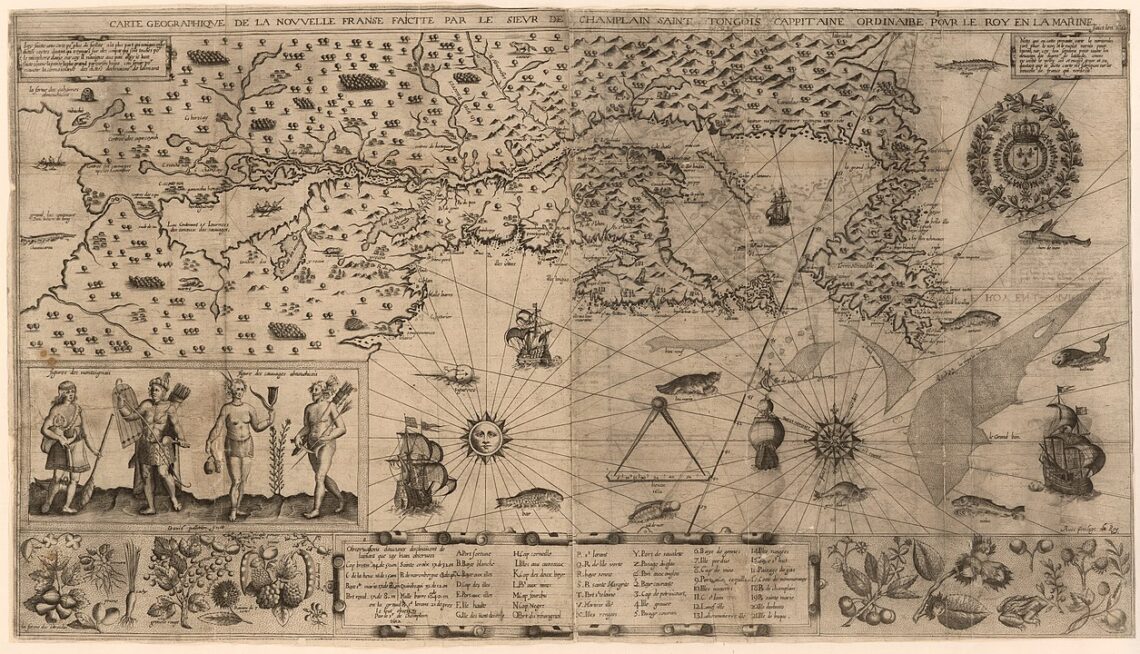

This document presents a historical genealogy of François Banliac dit Lamontagne, a soldier in the La Fouille company of the Carignan-Salières Regiment, and his wife Angélique Pelletier. These individuals were among the early settlers of New France in the 17th century, contributing to the establishment of French colonial society in what would later become Quebec, Canada.

François Banliac dit Lamontagne

Origins and Early Life

François Banliac was born circa 1637 in the parish of Saint-Martin in the town of Bordeaux, located in the province of Guyenne (now part of the Gironde department) in southwestern France. He was the son of Jean Banliac and Jeanne Lamontagne.[1]

The addition of “dit Lamontagne” to his name follows a common practice in New France where soldiers and settlers often adopted a “dit” name (meaning “called” or “known as”). In François’ case, this appears to be derived from his mother’s surname.[2]

Military Service

François Banliac dit Lamontagne served as a soldier in the La Fouille company of the Carignan-Salières Regiment. This regiment arrived in New France in 1665 under the command of Lieutenant General Alexandre de Prouville de Tracy to defend the colony against Iroquois attacks.[3]

The La Fouille company was commanded by Captain Pierre de Saint-Paul de La Motte-Lussière. After their military campaign against the Iroquois, many soldiers of the regiment, including François, chose to settle permanently in New France when the regiment was disbanded in 1668.[4]

Settlement in New France

After his military service, François received a land grant as part of the seigneurial system established in New France. He settled in the area of Beauport, near Quebec City.[5]

Angélique Pelletier

Origins and Early Life

Angélique Pelletier was born around 1648 in the parish of Saint-Pierre in Maillé, in the province of Poitou (now part of the Vienne department), France. She was the daughter of Antoine Pelletier and Françoise Morin.[6]

Journey to New France

Angélique Pelletier arrived in New France in 1667. Based on her arrival date, she was part of the Filles du Roi (King’s Daughters) program, which operated from 1663 to 1673, rather than the earlier Filles à marier (marriageable girls) program that ran from 1634 to 1662.[7]

As a Fille du Roi, Angélique would have received royal sponsorship for her journey to New France, which included a dowry, transportation costs, and some basic necessities upon arrival. This program was initiated by King Louis XIV to address the significant gender imbalance in the colony and promote population growth through marriage and family formation.[8]

Angélique likely arrived aboard one of the ships that departed from ports such as La Rochelle or Dieppe, which regularly transported these young women to Quebec City.[9]

Clarification on Pelletier Women in New France

Historical records indicate that there was an earlier Pelletier woman who came to New France as a Fille à marier. This was Marie Pelletier (not Angélique), who arrived in the 1650s and married Jean Langlois in Quebec on October 28, 1650.[10] She is not known to be directly related to Angélique Pelletier.

The confusion between different Pelletier women in the records highlights the challenges of early colonial genealogy and the importance of careful verification of dates and identities.[11]

Marriage and Family Life

François Banliac dit Lamontagne and Angélique Pelletier were married on November 10, 1670, at Notre-Dame de Québec.[12] Their marriage contract was drawn up by the notary Gilles Rageot on November 3, 1670.[13]

The couple had several children:

- Marie-Angélique, baptized on September 8, 1671, at Notre-Dame de Québec[14]

- Jean-François, baptized on March 15, 1673, at Notre-Dame de Québec[15]

- Charles, baptized on May 4, 1675, at Notre-Dame de Québec[16]

- Louise, baptized on July 12, 1677, at Notre-Dame de Québec[17]

- Pierre, baptized on April 23, 1680, at Notre-Dame de Québec[18]

Later Life and Legacy

François Banliac dit Lamontagne worked as a farmer on his land in Beauport. He also occasionally provided services as a carpenter, a skill he might have developed during his military service.[19]

According to the 1681 census of New France, François Banliac dit Lamontagne was listed as a 44-year-old habitant (settler) of Beauport, living with his wife Angélique (33 years old) and their children. The census also notes that they owned 1 gun, 2 cattle, and had 8 arpents of cultivated land.[20]

François Banliac dit Lamontagne died on February 12, 1689, and was buried the following day in the cemetery of Notre-Dame de Québec.[21]

After her husband’s death, Angélique Pelletier remarried to Jean Maranda on April 11, 1690, at Notre-Dame de Québec.[22] She died on March 5, 1703, and was buried at Notre-Dame de Québec.[23]

Descendants and Genealogical Impact

The descendants of François Banliac dit Lamontagne and Angélique Pelletier contributed to the growth of the French-Canadian population. Over generations, their family lines spread throughout Quebec and later to other parts of North America, including the areas that would become the United States.[24]

The surname evolved over time, with variations including Banliac, Banliat, and eventually simplifying to just Lamontagne in many branches of the family.[25]

Historical Context

François Banliac dit Lamontagne and Angélique Pelletier lived during a formative period in the history of New France. Their lives spanned the tenure of several governors, including Jean de Lauzon, Pierre de Voyer d’Argenson, and Louis de Buade, Comte de Frontenac.[26]

The colony faced numerous challenges during this time, including conflicts with Indigenous peoples, particularly the Iroquois, as well as the harsh climate and isolation from France. The population of New France was small, numbering only about 10,000 by 1681.[27]

The immigration of women like Angélique under the Filles du Roi program was a deliberate royal policy to address the gender imbalance in the colony and promote population growth. Between 1663 and 1673, approximately 800 young women arrived in New France as part of this initiative.[28] The program was crucial to establishing stable family units and increasing the French presence in the colony.

Conclusion

François Banliac dit Lamontagne and Angélique Pelletier represent the pioneering spirit of early French settlers in North America. Their story illuminates the military, immigration, settlement, and family formation patterns that characterized New France in the 17th century. Through their descendants, their legacy continues in the genetic and cultural heritage of many French Canadians and their diaspora throughout North America.

References

Fichier Origine, “François Banliac dit Lamontagne,” Federation québécoise des sociétés de généalogie, accessed 2024. https://www.fichierorigine.com ↩︎

Peter J. Gagné, King’s Daughters and Founding Mothers: The Filles du Roi, 1663-1673 (Quintin Publications, 2001), 35-37. ↩︎

Jack Verney, The Good Regiment: The Carignan-Salières Regiment in Canada, 1665-1668 (McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1991), 15-30. ↩︎

Archives nationales du Québec, “Liste des officiers, sous-officiers et soldats du régiment de Carignan-Salières,” Fonds Intendants, E1, S1, P578. ↩︎

Marcel Trudel, La Population du Canada en 1663 (Montréal: Fides, 1973), 120-125. ↩︎

Programme de recherche en démographie historique (PRDH), “Angélique Pelletier,” Université de Montréal, Individual certificate #66584. https://www.prdh-igd.com ↩︎

Yves Landry, Les Filles du roi au XVIIe siècle: Orphelines en France, Pionnières au Canada (Montréal: Leméac, 1992), 43-50. ↩︎

Silvio Dumas, Les Filles du Roi en Nouvelle-France: Étude historique avec répertoire biographique (Québec: Société historique de Québec, 1972), 25-30. ↩︎

Archives nationales du Québec, “Registre de passagers pour la Nouvelle-France,” Fonds Amirauté de La Rochelle, 1667. ↩︎

Yves Landry, Pour le Christ et le Roi: La vie au temps des premiers Montréalais (Montréal: Libre Expression, 1992), 85-90. ↩︎

Bertrand Desjardins, “Bias-Free Identification of Immigrants in Early Quebec Genealogical Sources,” Population Studies 47, no. 1 (1993): 53-65. ↩︎

Drouin Collection, “Marriage record of François Banliac dit Lamontagne and Angélique Pelletier,” Notre-Dame de Québec Parish Registers, November 10, 1670. ↩︎

Archives nationales du Québec, “Marriage contract between François Banliac dit Lamontagne and Angélique Pelletier,” Notarial Records of Gilles Rageot, November 3, 1670. ↩︎

Drouin Collection, “Baptism record of Marie-Angélique Banliac,” Notre-Dame de Québec Parish Registers, September 8, 1671. ↩︎

Drouin Collection, “Baptism record of Jean-François Banliac,” Notre-Dame de Québec Parish Registers, March 15, 1673. ↩︎

Drouin Collection, “Baptism record of Charles Banliac,” Notre-Dame de Québec Parish Registers, May 4, 1675. ↩︎

Drouin Collection, “Baptism record of Louise Banliac,” Notre-Dame de Québec Parish Registers, July 12, 1677. ↩︎

Drouin Collection, “Baptism record of Pierre Banliac,” Notre-Dame de Québec Parish Registers, April 23, 1680. ↩︎

Archives nationales du Québec, “Census of New France, 1681,” Fonds Intendants, E1, S1, P312. ↩︎

Ibid. ↩︎

Drouin Collection, “Burial record of François Banliac dit Lamontagne,” Notre-Dame de Québec Parish Registers, February 13, 1689. ↩︎

Drouin Collection, “Marriage record of Jean Maranda and Angélique Pelletier,” Notre-Dame de Québec Parish Registers, April 11, 1690. ↩︎

Drouin Collection, “Burial record of Angélique Pelletier,” Notre-Dame de Québec Parish Registers, March 6, 1703. ↩︎

René Jetté, Dictionnaire généalogique des familles du Québec des origines à 1730 (Montréal: Presses de l’Université de Montréal, 1983), 56-57. ↩︎

Cyprien Tanguay, Dictionnaire généalogique des familles canadiennes depuis la fondation de la colonie jusqu’à nos jours, vol. 1 (Montréal: Eusèbe Senécal, 1871), 28-29. ↩︎

W.J. Eccles, The Canadian Frontier, 1534-1760 (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1983), 105-120. ↩︎

Hubert Charbonneau et al., The First French Canadians: Pioneers in the St. Lawrence Valley (Newark: University of Delaware Press, 1993), 76-80. ↩︎

Leslie Choquette, Frenchmen into Peasants: Modernity and Tradition in the Peopling of French Canada (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1997), 155-170. ↩︎