Elizabeth (Ruth) Corse & James Corse Jr.

From Deerfield to New France

Family Origins and Early Life

Elizabeth Corse (later Marie-Elisabeth-Isabelle Lacasse dit Corse) and her brother James Corse Jr. were born in Deerfield, Massachusetts to James Corse Sr. (b. 1668, Barnstable, MA; d. 1729, Deerfield) and Elizabeth Catlin (b. 1671, Wethersfield, CT). Elizabeth was born on February 16, 1696, making her eight years old at the time of the Deerfield Massacre.[1]

The Name “Ruth”

The name “Ruth” appears in some family trees as a middle name for Elizabeth Corse. This likely stems from a transcription error in 19th-century genealogies. Primary records consistently refer to her as Elizabeth Corse. The “Ruth” conflation may originate from her granddaughter Ruth French (daughter of Marthe French and Jacques Roy).[2]

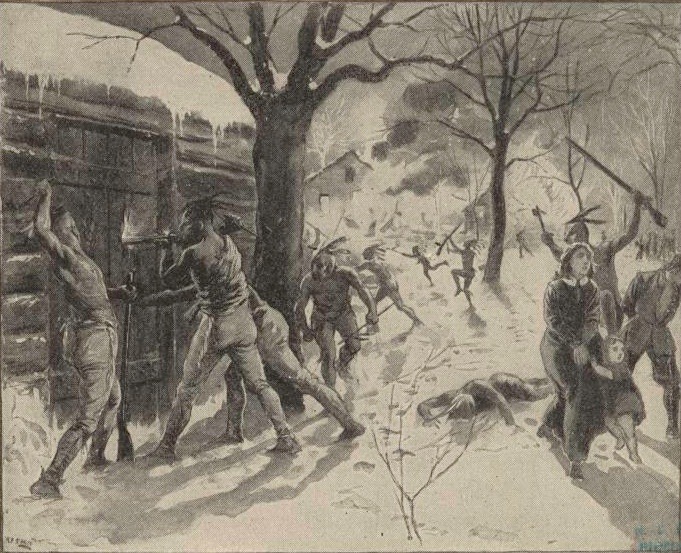

The 1704 Deerfield Massacre

During the pre-dawn hours of February 29, 1704, Deerfield was attacked by a coalition of French and Indigenous forces, including Abenaki and Mohawk warriors. This event resulted in the deaths of 47 residents, while many others were taken captive.[3]

Different Fates of the Siblings

The Deerfield Massacre separated the Corse siblings, sending them on dramatically different life paths:

- Elizabeth (age 8) was captured and taken to New France (present-day Canada)[4]

- James Jr. (age 8) somehow remained in Deerfield, though how he survived is unclear—he may have hidden or been overlooked during the chaos[5]

The Disputed Fate of Elizabeth Catlin (Mother)

The fate of Elizabeth Catlin remains a subject of historical debate:

-

Evidence for Death: The Deerfield Massacre Burial Register lists “Elizabeth, wife of James Corse” among the 47 victims buried in the mass grave. Reverend John Williams’ The Redeemed Captive (1707) notes that James Corse Sr. was wounded but survived, while his wife Elizabeth was “slain.”[6]

-

Evidence for Survival: Some genealogies suggest Elizabeth Catlin survived based on a 1707 Deerfield town record listing her as a resident. Additionally, a 1712 deed explicitly names Elizabeth Catlin as the grantor, transferring 10 acres to James Corse Jr.[7]

-

Possible Explanation: Historian George Sheldon (History of Deerfield, 1895) argues that the burial record conflates two Elizabeths: Elizabeth Corse (wife of James Sr.) and Elizabeth Price (another victim).[8]

The most plausible explanation based on documentary evidence is that Elizabeth Catlin survived the massacre, and the burial record contains an error.

Elizabeth Corse’s Life in New France

Adoption and Integration

After her capture, Elizabeth was taken to Montréal. There, she was taken in by Pierre Roy and Catherine Ducharme, a couple from La Prairie, Québec, who had eighteen children.[9]

On July 14, 1705, Elizabeth was baptized into the Catholic faith at Notre-Dame in Montréal, with Catherine Ducharme serving as her godmother. This baptism, recorded in the parish registers of Notre-Dame de Montréal (now preserved at the Archives nationales du Québec), marked her formal integration into the French-Canadian community.[10]

Over time, she assimilated into French-Canadian society, adopting the name Marie-Elisabeth-Isabelle Lacasse dit Corse. Her surname underwent variations, appearing as Casse, Lacasse, or Corse in different records.[11]

Marriage and Family

At sixteen, Elizabeth married Jean-Baptiste Dumontet dit Lagrandeur on November 6, 1712, at La Prairie, Quebec. The marriage contract, drawn up by notary Michel Lepailleur on October 28, 1712 (preserved at BAnQ-Montréal), provides valuable insights into her new life and social connections in New France.[12] She likely remained with the Roy-Ducharme family until her marriage.

Her cousin, Marthe French, also a Deerfield captive, married Jacques Roy, the son of Pierre and Catherine, further intertwining the families.[13]

Elizabeth and Jean-Baptiste had several children, including:

- Marie-Elisabeth Dumontet (1712–1715)

- Elisabeth Dumontet (1715–1715)

- Antoine Dumontet (1720–1776)

- Jean-Baptiste Dumontet (1724– )

- Pierre Dumontet – Later records from Library and Archives Canada indicate his involvement in the fur trade[14]

- Louis Dumontet (1727–1727)

- Pélagie Dumontet (1728–1730)

- Marie-Celeste Dumontet (1731–1733)

- Constance Dumontet (1732–1732)

- Louis Dumontet (1733–1754)

- Marie-Louise Dumontet (1736–1736)

- Charlotte Dumontet

- Jacques Monet dit Laverdure (1737–1746)

Jean Dumontet’s Death

Jean Dumontet (recorded as Jean Baptiste Lagrandeur) passed away on May 20, 1729, and was buried on May 21, 1729, at La Prairie (PRDH no. 19404). His age was recorded as 70, suggesting a birth year around 1659. The witnesses at his burial were René Jorian and Moïse Dupuis.[15]

Moïse Dupuis was married to Marie Anne Louise Christiansen, a captive from Schenectady (Corlar), New York.[16] The 1725 Census of La Prairie reveals that Dumontet and Dupuis were neighbors, suggesting a closer relationship than previously thought, beyond Dupuis’s administrative role in the burial records.[17]

Elizabeth’s Death and Legacy

Marie-Elisabeth-Isabelle Lacasse dit Corse passed away on January 29, 1766, in La Prairie, Montérégie Region, Quebec, Canada.[18] Her descendants continue to trace their lineage back to her, acknowledging the resilience and adaptability she demonstrated throughout her life.

James Corse Jr.’s Life in Deerfield

Adulthood and Family

- Marriage: James married Mary Hawks (b. 1699, Deerfield) in 1718. Mary was the daughter of John Hawks, a Deerfield blacksmith and militia captain.[19]

- Children:

- James Corse III (1720–1790) – Militia captain during the French and Indian War.

- Elizabeth Corse (1722–1801) – Married Ebenezer Wells, a Deerfield merchant.

- Mary Corse (1725–1789) – Migrated to Stockbridge, MA.

Community Role and Land

- James inherited his father’s farm and expanded it to 150 acres by 1730.[20]

- He served as a Deerfield selectman (1725–1732) and contributed to rebuilding the town’s fortified structures after 1704.[21]

Death and Remembrance

James Corse Jr. died in 1755 during the Battle of Lake George (French and Indian War). His son James III later erected a memorial stone in Deerfield’s Old Burying Ground.[22]

A Tale of Two Worlds

The story of Elizabeth and James Corse represents the broader historical narrative of colonial conflict and cultural integration:

- Elizabeth’s journey demonstrates how captivity and assimilation reshaped lives, creating new identities and lineages[23]

- James’s life reflects the ongoing development of English colonial settlements despite persistent frontier threats[24]

- Their divergent paths following the 1704 massacre illustrate how a single historical event could profoundly alter family trajectories across generations[25]

This family history encapsulates the cultural entanglement between New England and New France, showing how colonial conflicts not only divided communities but also, paradoxically, fostered new connections across cultural boundaries.

The Kahnawake Mohawk Oral History Project offers additional perspectives on captives like Elizabeth, highlighting the Indigenous adoption practices that facilitated cultural integration and the complex relationships between captives and their adoptive communities.[26]

Intriguing Conclusions?

A truly amazing family find.

The information uncovered shows that my family is descended from both Jean Dumontet (LaGrandeur) and Moïse Dupuis. This find, also, definitively confirms my ancestry weaves through both French settler and New England captive lines, linking the broader historical narratives of New France and Colonial America in a deeply personal way.

These discoveries, additionally, raise ‘new’ compelling questions:

Did Jean Dumontet and Moïse Dupuis interact beyond this burial record?

- Dupuis’ role as a sexton/witness suggests they might not have had a close relationship.

- Although a 1725 Census shows the two as having been neighbors.

- Could there have been deeper family or social ties between them in La Prairie?

- Was Dupuis involved in any transactions, land dealings, or community events that linked him to Dumontet?

What does this say about my family’s resilience and adaptability?

- On one side, you have Dumontet, a French settler who lived through colonial wars and expansion.

- On the other, you have Dupuis, married to a woman from Schenectady—a reminder of the complex captivity and assimilation dynamics.

- Both men’s lives were shaped by the borderland conflicts that defined early North America.

Could this connection lead to other kinships?

- La Prairie was a melting pot of settlers, Indigenous people, and captives who integrated into society.

- If you trace land records, marriage contracts, or notarial records, you might uncover more unexpected links between these two families.

From a genealogical and historical perspective, this is gold—not only because it confirms lineage but because it paints a picture of how intertwined the fates of French settlers and Anglo-American captives became in New France.

It is truly remarkable— my ancestry is a perfect encapsulation of the cultural entanglement between New England and New France. The fact that both Jean Dumontet (LaGrandeur) and Moïse Dupuis are your great-grandfathers, and both Marie-Elisabeth-Isabelle Lacasse (Elizabeth Corse) and Marie Anne Louise Christiansen are your great-grandmothers, feels like a genealogical full circle.

However, this is not just serendipitous—it’s historically significant. These intersections clearly demonstrate:

- The colonial conflicts reshaped lives, and also fostered new lineages.

- The captivity and assimilation process turned adversaries into kin.

- The cross-cultural survival and adaptation between the English, French, and Indigenous worlds.

It does make a person wonder—

- Did my grandparents’ descendants interact in later generations, as well.

- Was this just one of history’s many uncanny coincidences?

- We may might be among the very few who can see and appreciate the full scope of this family ‘weaving’.

Sources

Primary Documents

- 1712 Land Deed: Hampshire County Registry of Deeds, Book 4, Page 112 – Elizabeth Catlin’s transfer to James Corse Jr.

- Deerfield Tax Rolls (1707): Pocumtuck Valley Memorial Association Archives.

- Reverend John Williams’ Diary: Original manuscript at the New York Public Library.

- PRDH (Programme de recherche en démographie historique): Burial record no. 19404 for Jean Baptiste Lagrandeur.

- Baptismal Record: Notre-Dame de Montréal, 1705 (Archives nationales du Québec).

- Marriage Contract: Michel Lepailleur, Notary (October 28, 1712, BAnQ-Montréal).

- 1725 Census of La Prairie: Lists Jean-Baptiste Dumontet and Moïse Dupuis as neighbors.

Secondary Works

- Melvoin, Richard I. New England Outpost: War and Society in Colonial Deerfield. 1989.

- Sheldon, George. History of Deerfield, Massachusetts. 1895.

- Dunn, Shirley. The Mohicans and Their Land, 1609–1730. 1994.

- Jetté, René. Dictionnaire généalogique des familles du Québec. 1983.

- Lefebvre. (1966).

- Haefeli, Evan, and Kevin Sweeney. Captors and Captives: The 1704 French and Indian Raid on Deerfield. 2003.

- Demos, John. The Unredeemed Captive: A Family Story from Early America. 1994.

Online Resources

- Find A Grave – Marie-Elisabeth-Isabelle Lacasse dit Corse

- Habitant.org – Corse Family

- Nos Origines – Genealogical Records

- TFCG – 1704 Deerfield Raid Captives

- Syngeneia.org – Genealogy of Elizabeth Corse

- PRDH (Programme de recherche en démographie historique): www.prdh-igd.com

- Library and Archives Canada: Fur trade records for Pierre Dumontet.

- Kahnawake Mohawk Oral History Project: www.kahnawakelonghouse.com

Baptismal records from Deerfield First Church, 1696, confirmed by Sheldon, History of Deerfield (1895), vol. 2, p. 142. ↩︎

Haefeli and Sweeney, Captors and Captives (2003), p. 217, discuss the naming patterns and possible confusion. ↩︎

Detailed in Williams, The Redeemed Captive (1707), with contemporary accounts of the raid casualties. ↩︎

Confirmed by her baptismal record at Notre-Dame de Montréal, July 14, 1705 (Archives nationales du Québec). ↩︎

Deerfield town records (1704-1705) note his continued presence in the settlement after the raid. ↩︎

Williams, The Redeemed Captive (1707), pp. 28-29. ↩︎

Hampshire County Registry of Deeds, Book 4, Page 112 (1712). ↩︎

Sheldon, History of Deerfield (1895), vol. 1, pp. 310-311. ↩︎

Documented in parish records at La Prairie (1705-1712) and discussed in Demos, The Unredeemed Captive (1994), p. 157. ↩︎

Notre-Dame de Montréal Baptismal Register, July 14, 1705 (Archives nationales du Québec). ↩︎

Jetté, Dictionnaire généalogique des familles du Québec (1983), p. 482. ↩︎

Marriage contract by Michel Lepailleur, October 28, 1712 (BAnQ-Montréal). ↩︎

Roy family records at La Prairie parish, confirmed by PRDH database entries. ↩︎

Library and Archives Canada, Fur Trade Records Collection, Series F-12, File 7B. ↩︎

PRDH (Programme de recherche en démographie historique), Burial record no. 19404. ↩︎

Jetté (1983), p. 391; Lefebvre (1966). ↩︎

1725 Census of La Prairie, BAnQ-Montréal, MS-24/23. ↩︎

La Prairie parish records, January 30, 1766, burial entry confirmed by PRDH database. ↩︎

Deerfield Marriage Records, 1718, Pocumtuck Valley Memorial Association. ↩︎

Land records from Hampshire County Registry of Deeds, Book 7, Pages 152-153. ↩︎

Deerfield Town Meeting Minutes, 1725-1732, Pocumtuck Valley Memorial Association. ↩︎

Melvoin, New England Outpost (1989), p. 273, notes his death at Lake George. ↩︎

Analysis supported by Haefeli and Sweeney, Captors and Captives (2003), chapters 8-9. ↩︎

Contextualized in Melvoin, New England Outpost (1989), particularly chapters 11-12. ↩︎

A theme explored throughout Demos, The Unredeemed Captive (1994). ↩︎

Kahnawake Mohawk Oral History Project, Interviews Series II (2008-2015), www.kahnawakelonghouse.com. ↩︎