Catlin Family & the Deerfield Massacre

Introduction

Elizabeth (née Baldwin) Catlin, her husband James Catlin, and their family were among the many who suffered the devastating consequences of the 1704 Deerfield Massacre. Their story provides a poignant glimpse into the turbulent frontier of early New England, where settlers and Indigenous nations clashed in a struggle for survival and sovereignty.

The Catlin Family in Deerfield

James Catlin and Elizabeth Baldwin married in the late 17th century, settling in Deerfield, Massachusetts, a small but strategically significant frontier village. Like many in the region, the Catlins lived with the ever-present threat of conflict as tensions simmered between English settlers, French forces, and Indigenous groups, particularly the Mohawk and Abenaki, allied with New France.

Elizabeth was the daughter of John and Mary (Baldwin) Catlin. She married James Corse around 1690, and they had three children: Ebenezer, James Jr., and Elizabeth. James Sr. passed away on May 15, 1696, leaving Elizabeth a widow before the events of 1704.

The Deerfield Massacre (1704)

The Deerfield Massacre occurred in 1704 during Queen Anne’s War, part of the larger conflict known as the French and Indian Wars. In the early hours of February 29, 1704, a force of French soldiers and Indigenous warriors launched a surprise attack on Deerfield. The settlement’s defenses, weakened by winter’s hardships, crumbled quickly. Homes were burned, and many of the town’s residents—including women and children—were either killed or taken captive. Many settlers were killed, and over 100 were taken captive and marched to Canada. Many of the captives faced harsh conditions, and some were eventually redeemed or like John simply managed to return home.

The attack was carried out by French and Native American forces on the English settlement of Deerfield, Massachusetts.

- Over 50 settlers were killed.

- More than 100, including Elizabeth and her family, were taken captive and forced to march toward Canada.

- The town was largely destroyed by fire.

The Catlins’ fate was among the many tragic losses that night. Elizabeth Catlin and several of her children were either killed outright or perished in the arduous forced march toward Canada. Her parents, John and Mary Catlin, also suffered greatly—John was killed during the attack, and Mary died from the trauma. Additionally, four of their grown children and another grandson were killed during the massacre. The victims of the attack, including Elizabeth and her family, were laid to rest in a mass grave in Deerfield’s Old Burying Ground, where their remains still lie today, a solemn reminder of the tragedy.

COLERAINE, Nov. 1, 1875.

Mr. Sheldon:

DEAR SIR,—John Catlin, the captive, was born in the 50th year of his mother’s age, and never had slept out of his father’s house ‘till the age of 16, when he was taken captive, and went to Canada in company with a sister. His sister was very delicate, never had endured any hardship, but performed the journey so well that the Indians would give her something to carry; she would carry it a little way, and then throw it back as far as she could throw it. He (John) used to tremble for fear they would kill his sister, but they would laugh, and go back and get it. They acted as though they thought she was a great lady. The captives suffered from hunger, but she had plenty, and gave some to her brother. What her name was or what became of her I cannot tell. [Ruth, and she was redeemed.] He (John) was given to a French Jesuit. The Jesuit tried to persuade him to become a Catholic, but when he found he could not, told him he might go home when he had an opportunity; and when an opportunity presented, furnished him what he needed for the journey, and gave him some money when he parted with him. He was with him two years.

His father and uncle [brother Jonathan?] were killed in the house; he took his father’s gun, and his uncle’s powder horn, and was going to use them when the Indians took him. The captives were taken to a house, (I do not know what house) and a Frenchman* was brought in and laid on the floor; he was in great distress, and called for water; Mrs. Catlin fed him with water. Some one said to her, “How can you do that for your enemy?” She replied, “If thine enemy hunger, feed him; if he thirst, give him water to drink.” The Frenchman was taken and carried away, and the captives marched off. Mrs. Catlin was left. After they were all gone, a little boy came that was hid in the house. Mrs. Catlin said to the boy, “go run and hide.” The boy said, “Mrs. Catlin, why don’t you go and hide?” She said, “I am a captive; it is not my duty to hide, but you have not been taken, and it is your duty to hide.” Who this boy was I do not know. Some thought the kindness shown to the Frenchman was the reason of Mrs. Catlin’s being left.

LUCY D. SHEARER.

Analysis and Inferences:

- Elizabeth (Ruth) Catlin:

- Elizabeth, referred to as Ruth in the letter, was captured along with her brother John during the Deerfield Massacre. She was described as delicate but managed the journey to Canada well. The Native Americans treated her with a degree of respect, possibly due to her perceived status or demeanor.

- Contrary to earlier assumptions, Elizabeth was not redeemed and did not return to Deerfield. Instead, she remained in Canada, where she became known as Marie-Elisabeth-Isabelle Lacasse dit Corse.

- She married and had 13 children, indicating a deep level of assimilation into the French-Canadian community. By the time her brother John and his troop arrived in an attempt to rescue her, she had already established a new life in Canada.

- Elizabeth passed away on January 29, 1766, in La Prairie, Monteregie Region, Quebec, Canada.

- John Catlin:

- John was 16 when captured and taken to Canada. He was given to a French Jesuit who tried to convert him to Catholicism. When the Jesuit realized John would not convert, he allowed him to return home, providing him with necessities and money for the journey.

- John’s father and uncle were killed during the massacre. He attempted to defend himself using his father’s gun and uncle’s powder horn but was captured.

- Mrs. [Elizabeth] Catlin:

- Mrs. Catlin, likely John and Elizabeth’s mother, showed compassion by feeding a wounded Frenchman, despite him being an enemy. This act of kindness may have led to her being left behind when the captives were marched off. Note: [Elizabeth Catlin was and remains officially listed as having been killed during the massacre. She is reportedly buried in the mass grave.]

- She advised a young boy to hide, indicating her awareness of the danger and her resignation to her fate as a captive.

- Family Fate:

- The father and uncle were killed during the attack.

- Mrs. Catlin died in the massacre.

- John and Elizabeth were taken to Canada, with John eventually returning home.

Captivity and Survival

Among the captives taken northward was Elizabeth’s young daughter, also named Elizabeth, who would later be known as Marie-Elisabeth-Isabelle Lacasse dit Corse in Quebec. As was common with captives adopted into Indigenous or French Catholic communities, she assimilated into her new environment, eventually marrying Jean Dumontet and raising a large family. Her descendants became part of the fabric of French Canada, embodying the complex legacies of colonial-era conflicts.

In 1730, Elizabeth’s surviving son, James Jr., traveled to Canada in an unsuccessful attempt to bring his sister back home. By then, she had fully integrated into her new life and chose to remain in Canada.

Legacy and Historical Significance

The story of Elizabeth Baldwin Catlin and her family illustrates the volatility of life on the colonial frontier. Their experiences shed light on the broader struggles between European empires and Indigenous nations, as well as the personal tragedies and transformations wrought by these conflicts.

The Deerfield Massacre occurred within the larger context of Queen Anne’s War, one of a series of conflicts between France and England over control of North America. By preserving and sharing these histories, we ensure that the voices of those who endured such upheavals are not forgotten. Their legacy endures not just in historical records but in the lives of their many descendants who continue to seek out and honor their past.

References

- “The Mischief at Deerfield,” Massachusetts Historical Society

- “320 Years Ago: The Raid in Deerfield,” NHPR

- Raid on Deerfield 1704

- The 1704 Raid on Deerfield – The Canadian Encyclopedia

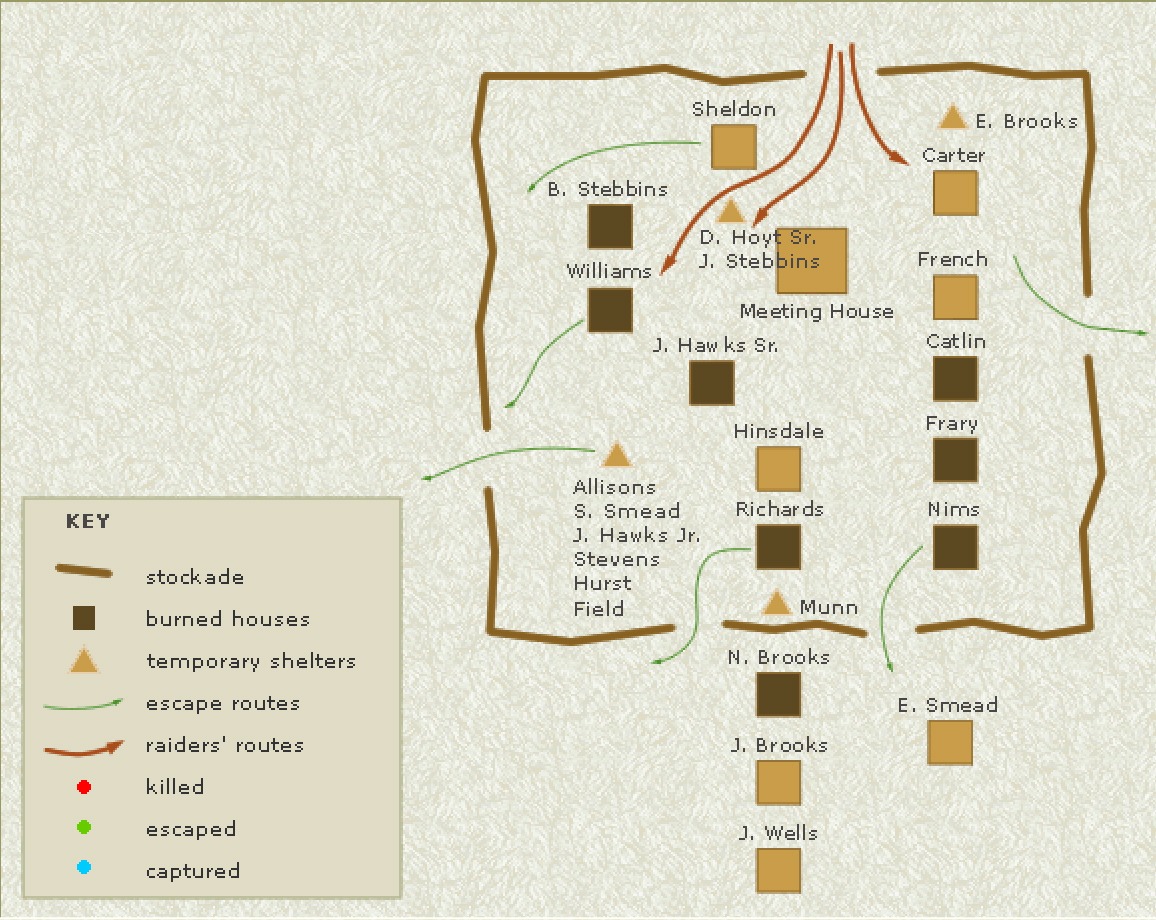

- The Deerfield Raid-A map showing how the raid was conducted and its aftermath.

- “1704 Deerfield Raid Captives,” Tsi Kiontakaton

- The Deerfield Massacre

- FamilySearch Profile of James Corse Sr.

- The Reverend Warham Williams and the Unredeemed Captive

- Queen Anne’s War: Raid on Deerfield

- Raid on Deerfield in Queen Anne’s War

- The Mischief at Deerfield

- Dudley Woodbridge journal, 1-10 Oct. 1728 “Within this 5-page journal Woodbridge described and sketched various meeting and dwelling houses in Watertown and Deerfield, Massachusetts“

All images used are the copyright of the original owner.

Based on our research each are allowed Fair Use protection at the time of acquisition.

Do you benefit from our articles and resources?

Your support, through donation or affiliate usage, allows ManyRoads to remain online.