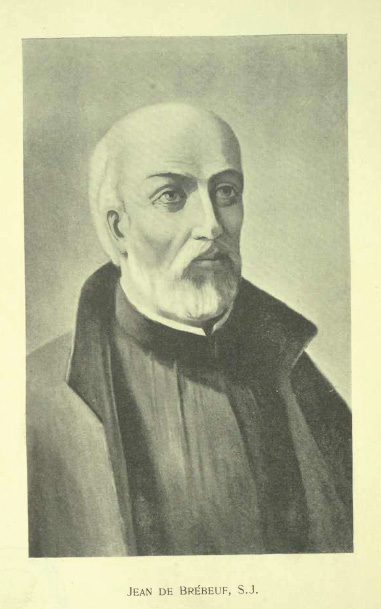

Jean de Brébeuf & Other Missionary Figures of the Compagnie de la Nouvelle France

Jean de Brébeuf (1593-1649): Missionary and Martyr

Early Life and Vocation

Jean de Brébeuf was born on March 25, 1593, in Condé-sur-Vire, Normandy, France, into a family of prosperous farmers. At age 24, he joined the Society of Jesus (Jesuits) as a lay brother, but his intellectual abilities were quickly recognized, leading him to be admitted to the priesthood track. He was ordained in 1622 after completing his theological studies.[1]

First Mission to New France

Brébeuf first arrived in New France in 1625, just two years before the Compagnie de la Nouvelle France was established. He was among the first Jesuits to work in the colony, where he immediately began studying the Huron (Wendat) language. His initial mission was cut short when the English captured Quebec in 1629, forcing him to return to France.[2]

Return and Work with the Huron

When the Treaty of Saint-Germain-en-Laye restored New France to French control in 1632, Brébeuf returned to resume his missionary work. As a member of the Compagnie de la Nouvelle France, which had explicit obligations to support missionary activities, Brébeuf benefited from the company’s resources as he established missions among the Huron people.[3]

Brébeuf lived among the Huron from 1634 to 1649, mastering their language and documenting their customs, religious beliefs, and daily practices. His ethnographic observations, particularly his detailed account of the Huron Feast of the Dead ritual, remain valuable historical and anthropological sources. He composed a Huron grammar and dictionary, tools that would prove invaluable for future missionaries.[4]

Missionary Approach and Cultural Sensitivity

Unlike some contemporaries, Brébeuf advocated for a relatively respectful approach to Indigenous customs. While clearly intent on conversion, he recognized the need to understand Huron culture deeply before attempting to introduce Christianity. He wrote:

“You must love these Huron, ransomed by the blood of the Son of God, with an intense love. You must identify with them, and nothing must be foreign to you; you must become Huron with the Huron to win them to Christ.”[5]

This approach was consistent with Jesuit missionary strategies but stood in contrast to some other religious orders’ methods. Brébeuf’s famous instructions to fellow missionaries working among the Huron reveal his practical wisdom and cultural sensitivity.

Martyrdom

The final years of Brébeuf’s life coincided with escalating conflicts between the Huron and Iroquois nations. On March 16, 1649, Iroquois warriors captured Brébeuf and his companion Gabriel Lalemant at the St. Louis mission. They were subjected to ritualized torture, with Brébeuf enduring extreme suffering before his death on March 16, 1649. Eyewitness accounts from Huron who escaped described the extreme tortures inflicted on him, which he reportedly endured with remarkable composure.[6]

Brébeuf was canonized as a saint by Pope Pius XI in 1930, along with seven other “North American Martyrs.” He is considered a patron saint of Canada and his feast day is celebrated on October 19 in Canada and September 26 in the United States.

Other Significant Missionary Figures Associated with the Compagnie

Charles Lalemant (1587-1674)

As the first Superior of the Jesuit mission in Quebec from 1625 to 1629, Charles Lalemant worked closely with the early leadership of the Compagnie de la Nouvelle France. His letters to his brother, a Jesuit provincial in France, generated interest and support for the mission. After being captured during the English occupation of Quebec, he returned to France where he helped recruit missionaries and raise funds. He later served three terms as rector of the Jesuit college in Paris, maintaining important connections between the metropolitan center and the colonial missions.[7]

Paul Le Jeune (1591-1664)

Le Jeune served as Superior of the Jesuit mission in New France from 1632 to 1639, during the crucial early years of the Compagnie de la Nouvelle France’s operations. His annual reports (Relations) were published in France and became popular reading, generating support for both the Jesuit missions and the colonial project generally. Le Jeune advocated for a settlement strategy that would place French colonists near Indigenous communities to facilitate conversion efforts—a policy that aligned with the Compagnie’s own settlement objectives.[8]

Isaac Jogues (1607-1646)

Another of the North American Martyrs, Jogues arrived in New France in 1636 and worked among both the Huron and the Montagnais peoples. Captured by the Mohawk in 1642, he suffered extreme torture before being ransomed by Dutch traders. Despite this experience, he voluntarily returned to Mohawk territory as a peace emissary in 1646, where he was killed. His connection to the Compagnie de la Nouvelle France was through the organizational and financial support the company provided to the Jesuit missions.[9]

Marie de l’Incarnation (1599-1672)

While not a Jesuit like the male missionaries listed above, Marie Guyart (known in religion as Marie de l’Incarnation) was a pivotal figure in the religious life of New France. As founder of the Ursuline convent in Quebec in 1639, she established the first school for girls in North America. The Compagnie de la Nouvelle France supported her work as part of its obligation to promote Catholic settlement and conversion. Her extensive correspondence provides valuable insights into life in the colony, and she is recognized for her work in learning and documenting Indigenous languages.[10]

Gabriel Lalemant (1610-1649)

Nephew of Charles Lalemant, Gabriel arrived in New France in 1646 and was assigned to assist Brébeuf at the Huron mission. Despite his relatively brief time in the colony, his martyrdom alongside Brébeuf became an important symbol of missionary dedication. The support he received from the Compagnie de la Nouvelle France facilitated his journey and mission work.[11]

Collective Impact of Missionary Activities

The missionaries associated with the Compagnie de la Nouvelle France had a profound and complex impact on the development of the colony and its relationships with Indigenous peoples:

-

Cultural Documentation: Their writings preserved valuable information about Indigenous languages, customs, and beliefs that might otherwise have been lost.

-

Colonial Infrastructure: Missions often served as nuclei for settlement and trade, advancing the Compagnie’s territorial ambitions.

-

Education: Mission schools established by these religious figures laid the foundation for formal education in New France.

-

Indigenous Relations: While missionaries often respected Indigenous cultures more than many colonists did, their fundamental goal of religious conversion nevertheless contributed to cultural disruption.

-

Metropolitan Connection: Their published accounts kept interest in New France alive in the metropolitan center, helping to maintain support for the colonial project.[12]

References

Talbot, Francis X. Saint Among the Hurons: The Life of Jean de Brébeuf. Harper & Brothers, 1949, pp. 3-12. ↩︎

Donnelly, Joseph P. Jean de Brébeuf, 1593-1649. Loyola University Press, 1975, pp. 25-37. ↩︎

Trigger, Bruce G. The Children of Aataentsic: A History of the Huron People to 1660. McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1976, pp. 502-507. ↩︎

Blackburn, Carole. Harvest of Souls: The Jesuit Missions and Colonialism in North America, 1632-1650. McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2000, pp. 105-112. ↩︎

Thwaites, Reuben Gold, ed. The Jesuit Relations and Allied Documents, Vol. 12. Burrows Brothers, 1898, p. 117. ↩︎

Parkman, Francis. The Jesuits in North America in the Seventeenth Century. Little, Brown, and Company, 1867, pp. 387-392. ↩︎

Campeau, Lucien. La Mission des Jésuites chez les Hurons: 1634-1650. Éditions Bellarmin, 1987, pp. 71-80. ↩︎

Deslandres, Dominique. Croire et faire croire: Les missions françaises au XVIIe siècle. Fayard, 2003, pp. 200-210. ↩︎

Anderson, Emma. The Betrayal of Faith: The Tragic Journey of a Colonial Native Convert. Harvard University Press, 2007, pp. 138-145. ↩︎

Davis, Natalie Zemon. Women on the Margins: Three Seventeenth-Century Lives. Harvard University Press, 1995, pp. 63-139. ↩︎

Latourelle, René. Étude sur les écrits de Saint Jean de Brébeuf. Presses de l’Université de Montréal, 1952, pp. 132-140. ↩︎

Greer, Allan. The Jesuit Relations: Natives and Missionaries in Seventeenth-Century North America. Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2000, pp. 13-27. ↩︎