Charles de Saint-Étienne de la Tour: Early Leader of New France

Early Life and Arrival in Acadia

Charles de Saint-Étienne de la Tour was born around 1593 in France, likely in the province of Champagne, to a family of minor nobility. His father, Claude de Saint-Étienne de la Tour, was a Huguenot (French Protestant) who had suffered financial reversals. Seeking to rebuild their fortunes, father and son came to Acadia around 1610, shortly after the initial settlements established by Pierre du Gua de Monts and Samuel de Champlain.[1]

The precise circumstances of their arrival are somewhat obscure, but they appear to have been associated with Jean de Biencourt de Poutrincourt et de Saint-Just, who was attempting to reestablish the settlement at Port Royal (now Annapolis Royal, Nova Scotia) after its temporary abandonment in 1607.[2]

Early Career in Acadia

As a young man, Charles de la Tour quickly adapted to life in Acadia. Unlike many European colonists who remained isolated from indigenous peoples, de la Tour immersed himself in the local context. He learned Mi’kmaq and other indigenous languages, developed extensive trade networks, and allegedly married a Mi’kmaq woman (whose name is not recorded in historical documents) early in his time in Acadia. This marriage, while not officially recognized in French records, appears to have been conducted according to Mi’kmaq customs and produced a daughter named Jeanne.[3]

Following the death of Biencourt around 1623, de la Tour emerged as one of the principal French leaders in Acadia. He established a trading post at Cape Sable (at the southern tip of Nova Scotia), which became his primary base of operations. From this location, he developed a profitable fur trade operation that connected him to both indigenous trappers and European markets.[4]

Complex Loyalties During Anglo-French Conflicts

De la Tour’s career was significantly shaped by the ongoing imperial rivalry between France and England in the North Atlantic. In 1627, war broke out between the two powers, with immediate implications for Acadia. That same year, the Compagnie de la Nouvelle France (Company of One Hundred Associates) was founded by Cardinal Richelieu to strengthen French colonial presence, with de la Tour becoming an associate of the company.[5]

In 1628, English forces under Sir David Kirke captured Quebec. The following year, Charles’ father Claude, who had been in England, returned to Acadia with English backing and attempted to persuade his son to transfer his allegiance to England. In a famous incident that has become part of Canadian historical lore, Charles reportedly refused his father’s entreaties, declaring his loyalty to France.[6]

Despite this declaration, Charles de la Tour’s actual allegiances appear to have been more pragmatic than the patriotic legend suggests. Throughout his career, he demonstrated a remarkable ability to navigate between competing imperial powers, sometimes holding commissions from both French and English authorities simultaneously. This flexibility was less a matter of treachery than a practical response to the uncertain political situation in a contested borderland.[7]

Leadership Role and Connection to the Compagnie de la Nouvelle France

In recognition of his control over key parts of Acadia, the French crown appointed de la Tour as Lieutenant General of Acadia in 1631. This appointment formalized his authority and connected him more directly to the imperial administration. As a member of the Compagnie de la Nouvelle France, he was expected to advance both trade and settlement in the region.[8]

His relationship with the company was complex. On one hand, he benefited from the official recognition and support it provided; on the other, the company’s monopolistic structure potentially threatened his independent trading activities. De la Tour appears to have sought to maintain as much operational autonomy as possible while leveraging the company’s resources when advantageous.[9]

Rivalry with d’Aulnay

The most dramatic chapter in de la Tour’s career was his protracted conflict with Charles de Menou d’Aulnay, another French nobleman active in Acadia. The origins of their rivalry lay in overlapping and ambiguous commissions granted by French authorities. In 1638, France divided Acadia into two jurisdictions, with d’Aulnay controlling the western portion (including Port Royal) and de la Tour the eastern section (centered on his new fortified trading post, Fort Sainte Marie, near present-day Saint John, New Brunswick).[10]

This attempt at administrative division failed to resolve tensions, and open hostilities erupted between the two men. The conflict had multiple dimensions:

- Commercial competition: Both men sought to control the lucrative fur trade

- Political authority: Each claimed superior legitimacy as the representative of French power

- Religious differences: D’Aulnay was a devout Catholic, while de la Tour (though nominally Catholic) came from a Protestant background and maintained more religiously diverse associations

- Approaches to Indigenous relations: De la Tour favored deep integration with Indigenous communities, while d’Aulnay pursued a more segregated model of colonization[11]

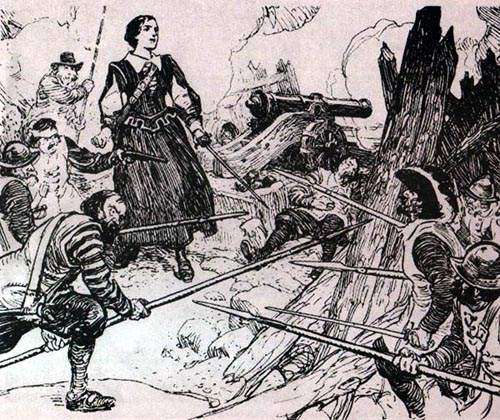

The conflict escalated into a civil war within Acadia. In 1645, while de la Tour was away seeking support in France, d’Aulnay attacked Fort Sainte Marie. In a famous episode, de la Tour’s second wife, Françoise-Marie Jacquelin (whom he had married in 1640), led the defense of the fort for three days before being forced to surrender. Despite promises of quarter, d’Aulnay allegedly forced Madame de la Tour to witness the execution of her garrison, after which she died within weeks, reportedly from the shock of these events.[12]

Later Career and Reconciliation

Following this defeat, de la Tour spent several years in exile, primarily in Quebec. His fortunes changed dramatically in 1650 when d’Aulnay drowned in a canoe accident. In a remarkable turn of events, de la Tour returned to Acadia, successfully petitioned the French crown for restoration of his titles and properties, and even married d’Aulnay’s widow, Jeanne Motin, in 1653—a pragmatic alliance that helped unify the rival factions.[13]

However, de la Tour’s restored position proved short-lived. In 1654, English forces under Robert Sedgwick conquered Acadia. Rather than resist, de la Tour once again demonstrated his pragmatism by accommodating the new regime. He traveled to England and, leveraging his past connections, secured recognition of his property rights. Together with English partners, he received a grant to much of Acadia from Oliver Cromwell.[14]

This arrangement lasted until 1667 when Acadia was returned to France through the Treaty of Breda. By this time, de la Tour—now in his seventies—had sold his rights to his English partners and retired from active involvement in colonial affairs. He died around 1666-1667, leaving behind a complex legacy.[15]

Legacy and Historical Significance

Charles de la Tour’s career provides a fascinating window into the fluid and contested nature of early European colonization in northeastern North America. Several aspects of his legacy deserve particular attention:

Colonial Leadership Style

De la Tour exemplified a distinctive early colonial leadership model that differed markedly from later, more institutional forms of authority. His power was based on personal relationships, intimate knowledge of local conditions, and adept cross-cultural negotiation rather than formal bureaucratic structures. This personalistic leadership style was particularly suited to the frontier conditions of early Acadia.[16]

Indigenous-European Relations

Perhaps more than any other French leader of his era, de la Tour embodied the interpenetration of European and Indigenous worlds. His first marriage into Mi’kmaq society, his linguistic abilities, and his willingness to adopt aspects of Indigenous diplomatic practices made him a crucial cultural intermediary. While he certainly pursued his own interests and those of the French crown, he did so through accommodation and alliance rather than mere imposition.[17]

Relationship with the Compagnie de la Nouvelle France

De la Tour’s involvement with the Compagnie de la Nouvelle France illustrates both the company’s reach and its limitations. As an associate of the company, he ostensibly operated within its framework, but his actual operations often proceeded with considerable independence. This pattern—company structures overlaid on more personalistic networks—characterized much of the company’s actual functioning in the field.[18]

National Memory

De la Tour has been remembered differently in various national traditions. In Canadian historiography, particularly in its Acadian strand, he has often been portrayed as a heroic founding figure who maintained French presence against English encroachment. In Quebec historiography, his willingness to accommodate English authority has sometimes been viewed more critically. In both traditions, however, his remarkable adaptability and cultural fluidity make him a figure who defies simple categorization.[19]

Contribution to Acadian Identity

For the Acadian people—the descendants of the French settlers in what is now Maritime Canada—de la Tour represents an important ancestral figure who helps explain the distinctive Acadian identity that developed in relative isolation from metropolitan France. His practical accommodations with various powers prefigured the complex neutrality that would characterize later Acadian relations with competing imperial forces.[20]

Conclusion

Charles de Saint-Étienne de la Tour stands as one of the most colorful and significant figures in the early history of New France. His career spanned a crucial transitional period when European presence in northeastern North America was shifting from tentative outposts to more established colonies. Through his connection to the Compagnie de la Nouvelle France, his entrepreneurial activities, his cross-cultural relationships, and his political maneuvering, he helped shape the distinctive character of early Acadian society and left an indelible mark on the region’s historical development.[21]

References

Reid, John G. “Charles de Saint-Étienne de La Tour.” Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 1, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 1966. ↩︎

Griffiths, N.E.S. From Migrant to Acadian: A North American Border People, 1604-1755. McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2005, pp. 31-34. ↩︎

Wicken, William C. Mi’kmaq Treaties on Trial: History, Land, and Marshall Junior. University of Toronto Press, 2002, pp. 43-47. ↩︎

Reid, John G. Acadia, Maine, and New Scotland: Marginal Colonies in the Seventeenth Century. University of Toronto Press, 1981, pp. 29-36. ↩︎

Trudel, Marcel. The Beginnings of New France 1524-1663. McClelland and Stewart, 1973, pp. 183-186. ↩︎

Daigle, Jean, ed. Acadia of the Maritimes: Thematic Studies from the Beginning to the Present. Chaire d’études acadiennes, Université de Moncton, 1995, pp. 21-24. ↩︎

Faragher, John Mack. A Great and Noble Scheme: The Tragic Story of the Expulsion of the French Acadians from Their American Homeland. W.W. Norton, 2005, pp. 46-51. ↩︎

Lanctot, Gustave. A History of Canada, vol. 1. Clarke, Irwin & Company, 1963, pp. 122-128. ↩︎

Allaire, Gratien. “Officiers et marchands: les sociétés de commerce des fourrures, 1715-1760.” Revue d’histoire de l’Amérique française, vol. 40, no. 3, 1987, pp. 409-428. ↩︎

MacBeath, George. “Charles de Menou d’Aulnay.” Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 1, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 1966. ↩︎

Baudry, René. “Madame de La Tour et les Récollets.” Revue d’histoire de l’Amérique française, vol. 4, no. 3, 1950, pp. 349-363. ↩︎

Griffiths, N.E.S. The Contexts of Acadian History, 1686-1784. McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1992, pp. 8-11. ↩︎

Reid, John G. Essays on Northeastern North America, Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries. University of Toronto Press, 2008, pp. 69-82. ↩︎

Barnes, Viola F. “The Rise of William Phips.” The New England Quarterly, vol. 1, no. 3, 1928, pp. 271-294. ↩︎

Clark, Andrew Hill. Acadia: The Geography of Early Nova Scotia to 1760. University of Wisconsin Press, 1968, pp. 102-108. ↩︎

Taylor, Alan. American Colonies: The Settling of North America. Penguin Books, 2001, pp. 153-158. ↩︎

White, Richard. The Middle Ground: Indians, Empires, and Republics in the Great Lakes Region, 1650-1815. Cambridge University Press, 1991, pp. 52-56. ↩︎

Banks, Kenneth J. Chasing Empire Across the Sea: Communications and the State in the French Atlantic, 1713-1763. McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2002, pp. 30-36. ↩︎

Conrad, Margaret R. and James K. Hiller. Atlantic Canada: A Region in the Making. Oxford University Press, 2001, pp. 38-43. ↩︎

Ross, Sally and Alphonse Deveau. The Acadians of Nova Scotia: Past and Present. Nimbus Publishing, 1992, pp. 11-15. ↩︎

Reid, John G. Six Crucial Decades: Times of Change in the History of the Maritimes. Nimbus Publishing, 1987, pp. 16-23. ↩︎